I just finished a fantastic book. At JB's 30th surprise party this past January, I asked everyone who wanted to bring a gift, to bring their favorite book! I, honestly, was thrilled with this idea, and will probably do it again in the future. John got some great books and has read many of them. He has yet to read The Kite Runner, a gift from our friends Tia and her fiancee' Rob. However, I am now done with it. I wish I wasn't. I wish the characters were still moving forward. I wish I could continue to look into their lives. There are so many things I still want to see them do.

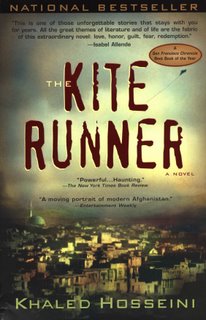

I just finished a fantastic book. At JB's 30th surprise party this past January, I asked everyone who wanted to bring a gift, to bring their favorite book! I, honestly, was thrilled with this idea, and will probably do it again in the future. John got some great books and has read many of them. He has yet to read The Kite Runner, a gift from our friends Tia and her fiancee' Rob. However, I am now done with it. I wish I wasn't. I wish the characters were still moving forward. I wish I could continue to look into their lives. There are so many things I still want to see them do.Now let me preface this glowing recommendation by telling you that this is not a light-hearted read. It is a very deep and moving book about a young Muslim boy growing up in Afghanistan during the last peaceful days of the monarchy, just before his country's revolution and its invasion by Russian forces. Written by Khaled Hosseini, he himself grew up in Afghanistan during the era that the book is set. He paints an amazing picture of a beautiful country torn apart by war.

It is also a mature read with very mature themes. The language is not too bad which I was thankful for, but the subject matter is very mature and definitely not for everyone. This was borderline "too deep" for me.

That being said, let me just say that Monday evening while JB was on call I laid in bed as 9:00 turned to 10 and 10 to 11 and 11 pushed its way toward midnight trying as hard as I could to get to a stopping point in this book -- a spot that I felt comfortable leaving the characters at until I could pick them up again. I finally did stop only to pick it up the next day during my lunch break and flip pages feverishly, attempting to finish before I had to return to work. It is actually completely irresistible. The characters are so beautifully painted and the descriptions so vivid that you keep forgetting this is not a biography -- forgetting that it is simply a piece of historical fiction. It is amazing, and if you can handle a deep, sad, and moving read, then give this a try.

WARNING! SPOILER AHEAD!

Okay, so if you plan to read the book, I'd suggest you stop reading this post immediately. I want to discuss a section of this book that really moved me due to its connection to infertility. This spoiler will not ruin the book but is definitely not preferable.

Midway through the book, the young couple, Amir and Soraya get married. As the years of their marriage ticked by, I immediately knew where this was going. Time to have the kids. I groaned a little internally knowing that yet again another couple would decide to try and "presto!" have a baby just like they tell you it happens in your health class in high school. Could anyone paint a realistic picture? That sometimes it doesn't happen like that?

I shouldn't have doubted this author's ability to paint a picture with the real world painted all over it. He painted the truth. That ometimes "Presto" isn't a magic word.

So I include a passage here. This passage so amazing represented what infertility is like in a few quick pages. It was quite breathtaking and emotional for me to read.

So I read:

That was the year that Soraya and I began trying to have a child.

The idea of fatherhood unleashed a swirl of emotions in me. I found it frightening, invigorating, daunting, and exhilarating all at the same time. What sort of father would I make, I wondered. I wanted to be just like Baba and I wanted to be nothing like him.

But a year passed and nothing happened. With each cycle of blood, Soraya grew more frustrated, more impatient, more irritable. By then, her mother's initially sublte hints had become over, as in "Kho dega!" So! "When am I going to sing alahoo for my little nawasa?" Her father, ever the Pashtun, never made any queries -- doing so meant alluding to a sexual act between his daughter and a man, even if the man in question had been married to her for over four years. But his eyes perked up when his wife teased us about a baby.

"Sometimes, it takes a while," I told Soraya one night.

"A year isn't a while, Amir!" she said, in a terse voice so unlike her. "Something's wrong. I know it."

"Then let's see a doctor."

Dr. Rosen, a round-bellied man with a plump face and small even teeth, spoke with a faint Eastern European accent, something remotely Slavic. He had a passion for trains -- his office was littered with books about the history of railroads, model locomotives, paintings of trains trundling on the tracks through green hills and over bridges. A sign above his desk read, LIFE IS A TRAIN, GET ON BOARD.

He laid out a plan for us. I'd get checked first. "Men are easy," he said, fingers tapping on his mahogany desk. "A man's plumbing is like his mind: simple, very few surprises. You ladies, on the other hand ... well, God put a lot of thought into making you." I wondered if he fed that bit about plumbing to all of his couples.

"Lucky us," Soraya said.

Dr. Rosen laughed. It fell a few notches short of genuine. He gave me a lab slip and a plastic jar, handed Soraya a request for some routine blood tests. We shook hands. "Welcome aboard," he said, as he showed us out.

***

I passed with flying colors.

The next few months were a blur of tests on Soraya: Basal body temperatures, blood tests for every conceivable hormone, urine tests, something called a "Cervical Mucus Test," ultrasounds, more blood tests, and more urine tests. Soraya underwent a procedure called a hysteroscopy -- Dr. Rosen inserted a telescope into Soraya's uterus and took a look around. He found nothing. "The plumbing's clear," he announced, snapping off his latex gloves. I wished he'd stop calling it that -- we weren't bathrooms. When the tests were over, he explained that he couldn't explain why we couldn't have kids. And, apparently, that wasn't so unusual. It was called "Unexplained infertility."

Then came the treatment phase. We tried a drug called Clomiphene, and hMG, a series of shots which Soraya gave to herself. When these failed, Dr. Rosen advised in vitro fertilization. We received a polite letter from our HMO, wishing us the best of luck, regretting they couldn't cover the cost.

We used the advance I had received for my novel to pay for it. IVF proved lengthy, meticulous, frustrating, and ultimately unsuccessful. After months of sitting in waiting rooms, reading magazines like Good Housekeeping and Reader's Digest, after endless paper gowns and cold, sterile exam rooms lit by fluorescent lights, the repeated humiliation of discussing every detail of our sex life with a total stranger, the injections and probes and specimen collections, we went back to Dr. Rosen and his trains.

He sat across from us, tapped his desk with his fingers, and used the word "adoption" for the first time.

Soraya cried all the way home.

Soraya cried all the way home.

Soraya broke the news to her parents the weekend after our last visit with Dr. Rosen. We were sitting on picnic chairs in the Taheris' backyard, grilling out and sipping yogart dogh. It was an early evening in March 1991. Her mother had watered the roses and her new honeysuckles, and their fragrance mixed with the smell of cooking fish. Twice already, she had reached across the chair to caress Soraya's hair and say, "God knows best, bachem. Maybe it wasn't meant to be."

Soraya kept looking down at her hands. She was tired, I knew, tired of it all.

A few months later, we used the advance for my second novel and placed a down payment on a pretty, two-bedroom Victorian house in San Francisco's Bernal Heights. Sometimes, Soraya sleeping next to me, I lay in bed and listened to the screen door swinging open and shut with the breeze, to the crickets chirping in the yard. And I could almost feel the emptiness of Soraya's womb, like it was a living, breathing thing. It had seeped into our marriage, that emptiness, into our laughs, and our lovemaking. And late at night, in the darkness of our room, I'd feel it rising from Soraya and settling between us. Sleeping between us. Like a newborn child.

(To read more ... buy the book. Or borrow it from me!)

(To read more ... buy the book. Or borrow it from me!)

No comments:

Post a Comment